Everybody has their “why.”

Whether you think about it or not, there’s a reason why you do what you do, and why you are who you are. It’s not just about your job or occupation or field, it’s about your story. Why do you even get up in the morning?

In a few weeks, the South Carolina Public Charter School District and I will be rolling out a podcast called “Kids First,” and it’s all about the “the why.” I’ll be sitting down with people who have a passion for education – teachers, administrators, parents, policy-makers – and asking them, “What’s your why?” I can’t wait to have some awesome conversations about education, choice, and the future of the classroom as a space that puts Kids First.

So, before I put anyone else on the spot, I thought I might go first and share my “why.” Why I work in education, and why I’m the last person who thought I would.

From learning difficulties to an Eagle Scout Project

I had learning difficulties early on in school; no definitive disabilities, just certain concepts that didn’t stick easily. In 5th grade, my school guidance counselor told me that because of these struggles I most likely wouldn’t go to college, so I should start focusing on competencies that would help me get a job. No other choices, no other options.

Family, Scouts, and church were the foundation of my childhood. I was born into a Scouting family; my dad had been a Scoutmaster since before I was born. Each Christmas our troop would work with the Midlands Center, a state facility in Columbia that served adults with intellectual disabilities. We would visit, throw them a holiday party, and make them feel a part of our troop.

I was drawn to the people there, and to how the Center was giving them an opportunity to thrive.

So, in 1983, when I was 15 and aiming to become an Eagle Scout, I knew I wanted to work with this group again. Becoming an Eagle Scout required planning and leading a service project. My assistant Scoutmaster and I worked with the Midlands Center to organize and execute an event similar to the Special Olympics. I had no idea that this event, and these people, would be the seed that would produce a passion for education years later.

A few years later, with my Eagle Scout badge and high school diploma in hand, I proved that guidance counselor wrong. I completed my bachelor’s degree at the University of South Carolina, then pursued an extensive career in public affairs and government relations. For over 20 years I did just about everything one can do in this space – from campaign management at the state and national levels to representing corporate entities like Walmart, to starting a consulting firm to help bring manufacturing back to the US.

Afghanistan and education as liberation

Somewhere in the middle of all that policy-oriented work I felt called to join the military.

I joined the South Carolina State Guard as a volunteer in May of 2001, but four months later 9/11 occurred, and everything changed for me. I, like many others, felt convicted by the national tragedies to serve my country. So, I went down to the recruiting station and enlisted in the United States Navy at age 34. Seven and half years later I transferred to the Army National Guard. And in 2010, I received a surprising phone call from my commander summoning me to serve on a civil affairs team in Afghanistan for a year.

My wife and kids were shocked at the sudden news, but they supported me. So, three weeks later, I was on a military transport plane headed to Afghanistan during one of the most difficult periods of conflict there.

Our work in Afghan villages was humanitarian-aid focused. As an effort to build trust and integrate with community members, we built schools that opened the doors of education to young girls and clinics for women who had no access to healthcare; Taliban restrictions had prevented girls from even going to school up until then.

For these Afghan women, education was liberation. Education was finally having a choice in the outcome of their lives. As I taught – for the first time – in those ragged classrooms, halfway across the world, my passion for education was ignited.

Upon returning home to Arkansas in 2011, I resumed my position at Walmart, then later I proceeded to build my own company, Made In USA Works. But, I continued to think about those Afghan girls and the impact that access to education had on their lives.

All thanks to Marsh...and JFK.

In 2015 my youngest son, Marsh, was born with Down Syndrome. My life had come full circle to the experiences I shared with the people at the Midlands Center many years ago.

We spent the first few months of his life at the Children’s Hospital in Arkansas as he endured various surgeries and treatments. We quickly realized we would need to move closer to our family in South Carolina. That’s when I saw the job posting for a School Leader position at the Meyer Center in Greenville, a charter school for young children with intellectual disabilities.

I knew nothing about the center, but I applied for the position.

Over email, I explained that I had no experience in education, but that I had a son with Down Syndrome, and I wanted to be a part of what they were doing. I interviewed, got the job, and we moved to Greenville. For two and half years I got to take Marsh to work with me as he received various therapies and schooling. For two and half years I got to engage with the fantastic students and dedicated community at the Meyer Center.

And then one day, during my time there, I received a call from the White House.

They had heard about my story and were recruiting me to serve on the President’s Committee for People with Intellectual Disabilities. This was a committee created by President Lyndon Johnson but inspired by President John F. Kennedy, whose sister Rosemary had intellectual disabilities. He and his brother, Bobby, did extensive work to improve opportunities for disabled individuals.

I was honored to participate in this storied legacy as the Chairman of the Committee and I was humbled to think about how far I had come from the Midlands Center and my Eagle Scout project.

When I left the Meyer Center, we moved back to Columbia, and I started a position at a local law firm working on policy for a few local clients (including the South Carolina Public Charter School District). As we transitioned to Columbia, my wife and I were eager to find a school like the Meyer Center that would meet Marsh’s needs.

The public elementary school he was zoned for was a great school by most standards but offered very few opportunities for Marsh to be integrated with his classmates. We knew we didn’t want him to be isolated from other kids. We were blessed enough to be able to find and afford a small private school that could support him. But, after a year there, the school leader informed us that they wouldn’t be able to meet his needs anymore. We were out of yet another school.

This process was difficult and discouraging, and unfortunately, it’s not a unique story: Marsh was zoned for a school that was considered a great school by most metrics – but it was not a great school for him.

We needed a different option. We needed a choice.

At a crossroads and unsure of what to do, I reached out to the Erskine Charter Institute, who pointed us to Clear Dot Charter. Clear Dot is a Title I, inner-city school in downtown Columbia, and we loved their philosophy on classroom integration for all kids. We interviewed with the school leader, were accepted, and Marsh has been thriving there ever since.

During the early months of the Covid-19 Pandemic, the South Carolina Public Charter School District’s superintendent stepped down. At the time, I had been working closely with their board through the law firm. They knew my story, my charter school experience, and my passions, so they encouraged me to put my name in the hat for the new superintendent position.

And I did. And I got the job.

Sometimes, when you look backward, things fall into place. You can see how you got where you are – how you became who you are.

Throughout my life, I have seen and dealt with the pain that a lack of access and a lack of choice in education can cause. But I have also seen the beauty and joy that educational autonomy can provide.

I have felt the pain of an unsupported child as I struggled through elementary school, told by authority figures in school that I “didn’t have what it takes.”

I have felt the pain of an anxious parent as I fought to find an effective fit for my wonderfully unique child.

But I have seen the beauty of individuality celebrated in the faces of the people at the Midlands Center during my Eagle Scout Project.

I have seen the joy that freedom and knowledge bring in the Afghan girls attending school for the first time in their lives.

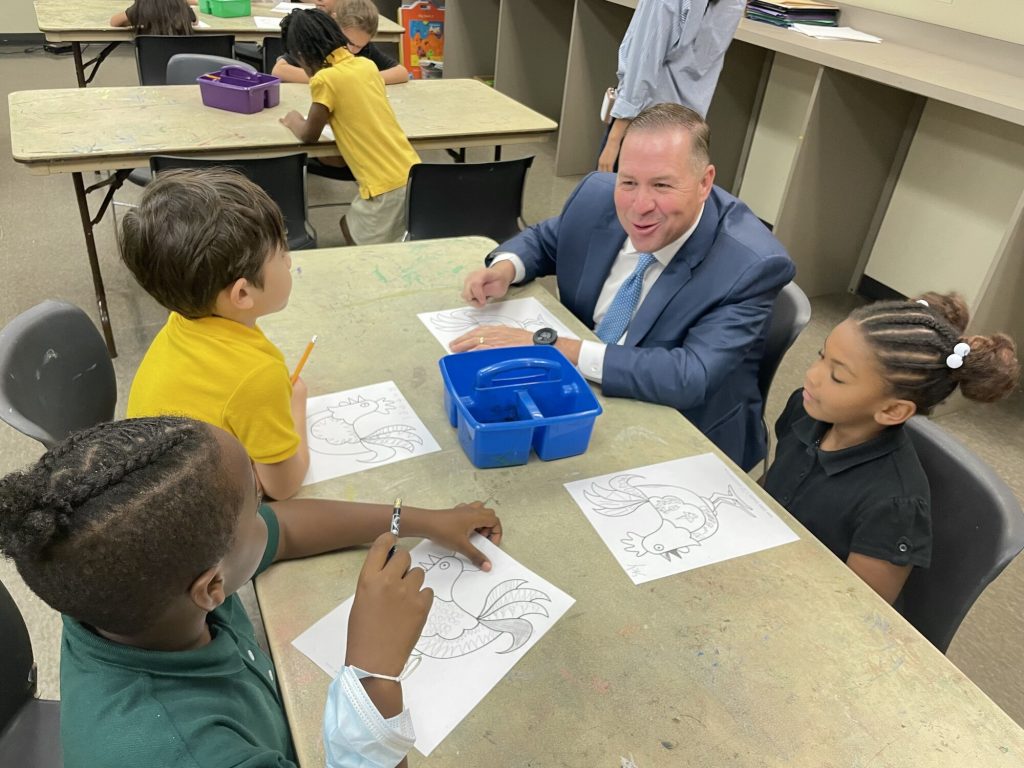

And I see it daily now – in the freedom, creativity, and ingenuity of all the kids in our charter schools. I am so thankful for the opportunity to serve this District. To make education mean more to kids than just test scores and GPAs. To give teachers autonomy in their classrooms. To give parents the freedom of choice.

Because choice is everything, and learning is opportunity, and every kid only gets one shot.

More to come — stay tuned.

So there’s my “why.”

Thank you for taking the time to read a little bit about me and why I do what I do. But this is hardly about me, and it is only the beginning.

Keep an eye out for the Kids First Podcast over the next few months! I can’t wait to continue listening to our students, parents, teachers, administrators, and policy-makers to learn more about their “why” – to hear their stories, and to hear more about how education has impacted their lives.

Kids First,

Chris Neeley